In the closing Winter Lecture for the London Review of Books, Terry Eagleton discusses the origin and uses of culture. Half-way through the piece, Fran Lock and Alan Morrison provide a complementary chorus of new poems. We are deeply grateful to the LRB and 'the dreadful Terry Eagleton', as King Charles called him, for their kind permissions to republish his lecture.

In Jude the Obscure, Jude Fawley finds himself living in Beersheba, the area of Oxford we know as Jericho, home at the time to a community of craftsmen and artisans who maintained the fabric of the university. It doesn’t take Jude long to realise that he and his fellow craftsmen are, so to speak, the material base without which the intellectual superstructure of the colleges couldn’t exist: without their work, as he says, ‘the hard readers could not read, nor the high thinkers live.’

He comes to recognise, in a word, that the origin of culture is labour. This is true etymologically as well. One of the original meanings of the word culture is the tending of natural growth, which is to say agriculture, and a cognate word, coulter, means the blade of a plough. The kinship between culture and agriculture was brought home to me some years ago when I was driving with the dean of arts of a state university in the US past farms blooming with luxuriant crops. ‘Might get a couple of professorships out of that,’ the dean remarked.

This is not the way culture generally likes to see itself. Like the Oedipal child, it tends to disavow its lowly parentage and fantasise that it sprang from its own loins, self-generating and self-fashioning. Thought, for idealist philosophers, is self-dependent. You can’t nip behind it to something more fundamental, since that itself would have to be captured in a thought. Geist goes all the way down.

There’s an irony here, since few things bind art so closely to its material context as its claim to stand free of that context. This is because the work of art as autonomous and self-determining, an idea born sometime in the late 18th century, is the model of a version of the human subject that has been rapidly gaining ground in actual life. Men and women are now seen as authors of themselves, as a result of the deepening influence of liberalism and possessive individualism and – to perpetrate a dreadful cliché – the rise of the middle classes. (If you open a history book at random, it will say three things about the period you light on: it was essentially an age of transition; it was a period of rapid change; and the middle classes went on rising. That’s the reason God put the middle classes on earth: to rise like the sun, but, unlike the sun, without ever setting.)

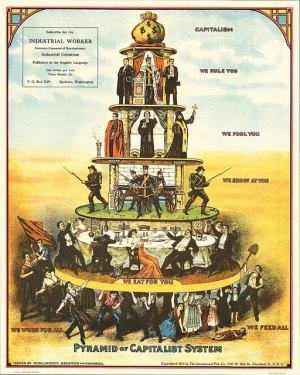

You can’t have culture in the sense of galleries and museums and publishing houses unless society has evolved to the point where it can produce an economic surplus. Only then can some people be released from the business of keeping the tribe alive in order to constitute a caste of priests, bards, DJs, hermeneuticists, bassoon players, LRB interns, gaffers on film sets and the like. In fact, you might define culture as a surplus over strict need. We need to eat, but we don’t need to eat at the Ivy. We need clothes in cold climates, but they don’t have to be designed by Stella McCartney. The problem with this definition is that a capacity for surplus is built into the human animal. For both good and ill, we’re continually in excess of ourselves. Culture is reckoned into our nature. King Lear is much concerned with this ambiguity.

Wanted: Culture, to legitimate the social order......

Since the material production that gives birth to culture is racked by conflict, bits of this culture tend to be used from time to time to legitimate the social order that strives to contain or resolve the conflict, and this is known as ideology. Not all culture is ideological at any given time, but any part of it, however abstract or high-minded, can serve this function in specific circumstances. At the same time, however, culture can muster vigorous resistance to the dominant powers.

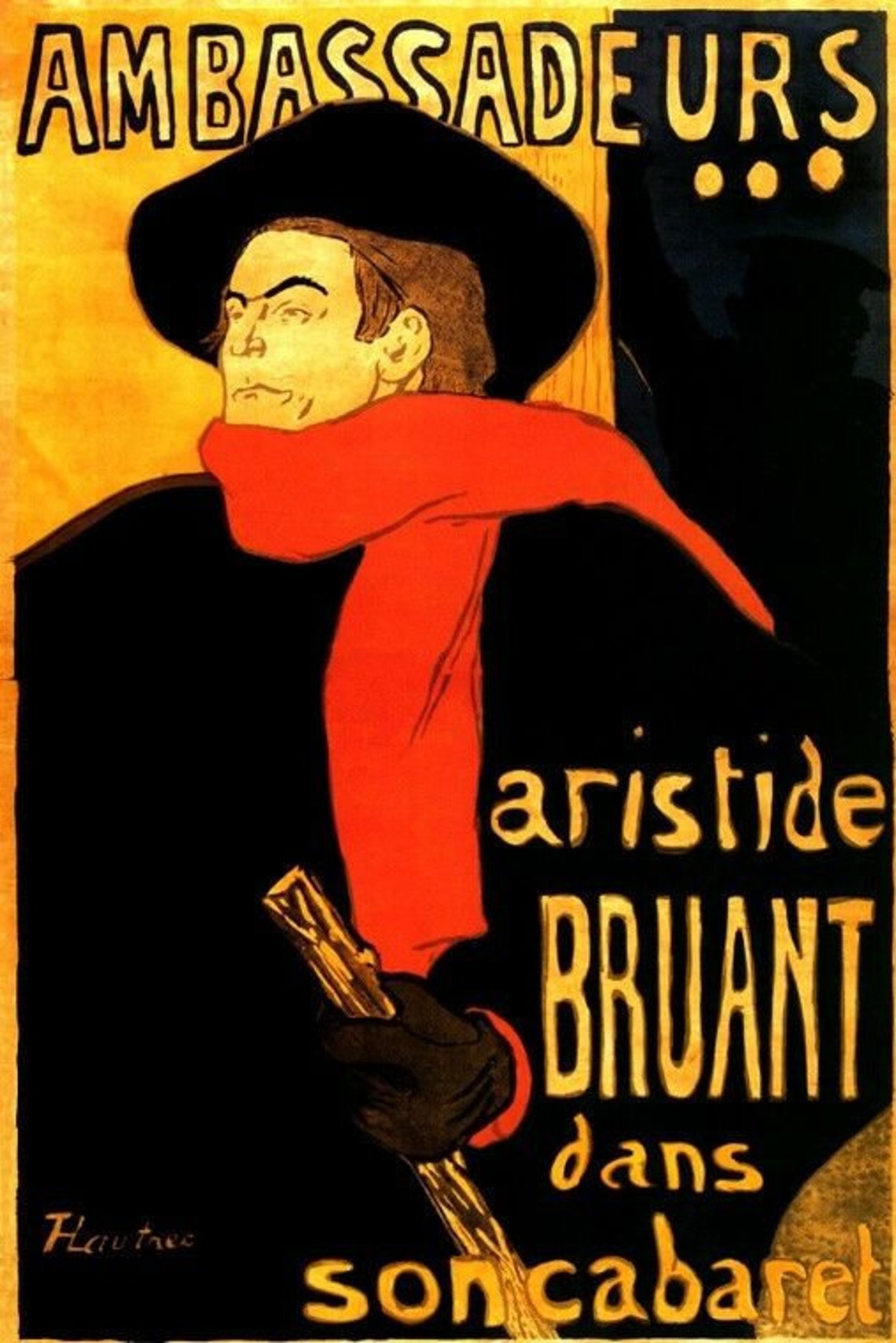

Banksy musters some vigorous resistance to the dominant powers

This resistance is more likely to occur, curiously enough, once art becomes just another commodity in the marketplace and the artist just another petty commodity producer. Before that, in traditional or pre-modern society, culture generally serves as an instrument of political and religious sovereignty, which means among other things that there are steady jobs for cultural workers as court poets, genealogists, licensed fools, painters and architects patronised by the landed gentry, composers in the pay of princes and so on. In those situations you also know more or less whom you are writing or painting for, whereas in the marketplace your audience becomes anonymous.

The world no longer owes the cultural worker a living. Ironically, however, it’s the integration of art into the market that gives it a degree of freedom. Once it’s primarily a commodity, culture becomes autonomous. Deprived of its traditional features, it may curve back on itself, taking itself as its own raison d’être in the manner of some modernist art; it is also free to serve as critique on a sizeable scale for the first time. The miseries of commodification are also an enthralling moment of emancipation. History, as Marx reminds us, progresses by its bad side. In the very process of being pushed to the margin, the artist begins to claim visionary, prophetic, bohemian or subversive status – partly because those on the edges can indeed sometimes see further than those in the middle, but also to compensate for a loss of centrality. A movement called Romanticism is born.

....and so capitalism gives culture a job to do

At roughly the same time, so is industrial capitalism, which with admirable convenience gives culture a job to do just as it’s in danger of being driven out by philistine mill-owners. There’s now a growing divide between the symbolic realm and the world of utility, a divide that runs all the way down the human body. Values and energies for which there isn’t much call in the workaday world of bodily labour are siphoned off into a sphere of their own, which consists of three major sectors: art, sexuality and religion. One of these endangered values is the creative imagination, which was invented in the late 18th century and is nowadays revered among artistic types, though organising genocide in Gaza requires quite a lot of it too.

The distance that opens up between the symbolic and the utilitarian, while threatening to rob culture of its social function, is also the operative distance you need for critique. Culture would expose the crippled, diminished condition of industrial-capitalist humanity through its full and free expression of human powers and capacities, a theme that runs from Schiller and Ruskin to Morris and Marcuse. Art or culture can issue a powerful rebuke to society not so much by virtue of what it says but because of the strange, pointless, intensely libidinal thing that it is. It’s one of the few remaining activities in an increasingly instrumentalised world that exists purely for its own sake, and the point of political change is to make this condition available to human beings as well. Where art was, there shall humanity be.

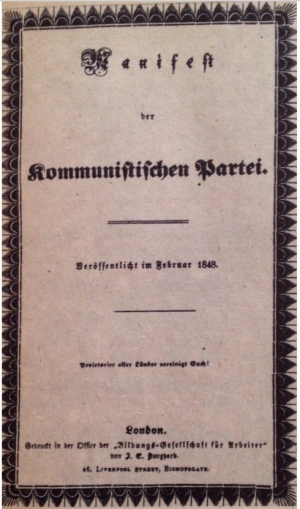

PCS workers issuing a powerful rebuke to society

The harmonious realisation of one’s powers as a delightful end in itself: if this is what the aesthetic comes to be about, it’s also the ethics of Romantic humanism, which includes the ethics of Karl Marx. The aesthetic becomes important when it isn’t simply about art. Marx’s thought concerns the material conditions that would make life for its own sake possible for whole societies, one such condition being the shortening of the working day. Marxism is about leisure, not labour. The only good reason for being a socialist, apart from annoying people you don’t like, is that you don’t like to work. For Oscar Wilde, who was closer in this respect to Marx than to Morris, communism was the condition in which we would lie around all day in various interesting postures of jouissance, dressed in loose crimson garments, reciting Homer to one another and sipping absinthe. And that was just the working day.

Half in love with the powers that repress us? Image by kennardphillips

There are problems with this vision, as there are with any ethics. Are all your powers to be realised? What about that obsessive desire to beat up Tony Blair? Or should one realise only those impulses that spring from the authentic core of the self? But by what criteria do we judge this? What if my self-realisation clashes with yours? And why should all-round expression beat devoting oneself to a single cause, like Alexei Navalny or Emma Raducanu? Do human capabilities really grow malevolent only by being alienated, lopsided or repressed? And what if we’re half in love with the powers that alienate and repress us, installed as they are inside the human subject rather than purely external to it?

Hegel and Marx have an answer of a kind to the problem of clashing self-fulfilments, which goes like this: realise only those capabilities which allow others to do the same. Marx’s name for this reciprocal self-realisation is ‘communism’. As the Communist Manifesto puts it, the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all. When the fulfilment of one individual is the ground or condition of the fulfilment of another, and vice versa, we call this love.

And the hands that act on it...

by Fran Lock

their charnel austerity, logged in the body.

a city repellent to memory, walk. this bleak

referendum of razors, indifferent justice,

law like a nail knocked into hunger. the law

is a meat-hook with your name on it, kid.

breathe. with the rhythm of syndrome,

the dark particulate scraped from a lung.

breathe. stertor, stridor, inspiratory stress.

productive cough that closes the throat.

their mouths are feudal thresholds. have

alphabets, inscribed against empathy.

say: this is the world, and what're you

going to do about it? step out. step out

of step. break that masochists pact,

patterned into apathy: work-or-death

and worked-to-death. the moment

becomes the movement, the moment

we decide to move. flip this tyranny

of tyrian shekels; pathologies of profit,

their sick vocations of control. love.

as conspicuous sabotage, direct action,

conductor of heat and dissonance. in

a world we cannot occupy or exit, be

the hand that lights the match, the arm

that bears the torch.

Marxism is about political love. I mean love, of course, in its real sense – agape, caritas – not the sexual, erotic, romantic varieties by which late capitalist society is so mesmerised. We’re speaking of the kind of love that can be deeply disagreeable and isn’t necessarily to do with feeling, that is a social practice rather than a sentiment, and which is in danger of getting you killed.

Agape

by Alan Morrison

agape - agape - agape -

love without possessiveness

platonic love

spiritual love

political love

love without possessions

love unfettered by desire

love without covetousness

love without expectation

hearts without property

hearts freed from property

love devout in poverty

agape - agape - agape -

love as common ownership

unconditional love

universal love

communism of souls

souls in common ownership

hearts & souls in fellowship

no hedges in heaven

only untethered purple heathland

lavender heather

lavender ever

& ever

love as common good

numinous communism

eudemonia -

welfare of all

capitalism can never

make us happy

pits us against ourselves

in pursuit of profit

& empty property

only love without covetousness

love without possessiveness

love for one & all

universal

unconditional

can approach that utopian

conception to be happy

agape - agape - agape -

Wanted: Culture, to buy off anarchy

Early industrial capitalism had another mission for culture to accomplish. A new actor had just appeared on the political scene – the industrial working class – and was threatening to be obstreperous. Culture, in the sense of the refined and civilised, was needed to buy off the other half of Matthew Arnold’s title, anarchy. Unless liberal values were disseminated to the masses, the masses might end up sabotaging liberal culture. Religion had traditionally bred a sense of duty, deference, altruism and spiritual edification in the common people. But religious belief was now on the wane, as the industrial middle classes demythologised social existence through their secular activities and, ironically, ended up depleting what had been a precious ideological resource. Culture, then, had to take over from the churches, as artists transubstantiated the profane stuff of everyday life into eternal truth.

What else was happening around the time of Romanticism and the industrial revolution? The revolution in France. One might do worse than claim that this was what thrust culture to the fore in the modern age – but culture as a riposte to the revolution, as an antidote to political turbulence. Politics involves decision, calculation, practical rationality, and takes place in the present, whereas culture seems to inhabit a different dimension, where customs and pieties evolve for the most part spontaneously, unconsciously, with almost glacial slowness, and may therefore pose a challenge to the very notion of throwing up barricades.

The name for this contrast in Britain is Edmund Burke, who came from a nation, Ireland, where the sovereign power had failed to root itself in the affections of the people because it was a colonialist power. In Burke’s view, this rooting wasn’t happening in revolutionary France either, since the Jacobins and their successors didn’t understand that if the law is to be feared, it is also to be loved. What you need in Burke’s opinion is a law which, though male, will deck itself out in the alluring female garments of culture. Power must beguile and seduce if it isn’t to drive us into Oedipal revolt. The potentially terrifying sublimity of the masculine must be tempered by the beauty of the feminine; this aestheticising of power, Burke writes in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, is what the French revolutionaries calamitously failed to achieve. You mustn’t, to be sure, aestheticise away the masculinity of the law. The ugly bulge of its phallus must be visible from time to time through its diaphanous robes, so that citizens may be suitably cowed and intimidated when they need to be. But the law can’t work by terror alone, which is why it must become a cross-dresser.

Edmund Burke pontificating against the French Revolution

Burke believed that the cultural domain – the sphere of customs, habits, sentiments, prejudices and the like – was fundamental in a way that the politics to which he devoted a lifetime were not, and he was right to think so. There have been some suspect ways of elevating the cultural over the political, but Burke, who began his literary career as an aesthetician, neither despises politics from the Olympian standpoint of high culture, nor dissolves politics into cultural affairs. Instead, he recognises that culture in the anthropological sense is the place where power has to bed itself down if it is to be effective. If the political doesn’t find a home in the cultural, its sovereignty won’t take hold. You don’t have to detest the Jacobins or idealise Marie Antoinette to take the point.

Despite his aversion to Jacobinism, Burke ended up feeling some sympathy for the revolutionary United Irish movement, an extraordinary sentiment for a British Member of Parliament. The Irish playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, also an MP, was even more dedicated to the United Irish cause. He was, in fact, a secret fellow-traveller – a fact that, had it been widely known, might have wiped the smiles off the faces of his London audiences. The United Irishmen were Enlightenment anti-colonialists, not Romantic nationalists, but the rise of Romantic nationalism in the early 19th century once more brought culture to the centre of political life.

Nationalism was the most successful revolutionary movement of the modern age, toppling despots and dismantling empires; and culture in both its aesthetic and anthropological senses proved vital in this project. With revolutionary nationalism, culture in the sense of language, custom, folklore, history, tradition, religion, ethnicity and so on becomes something people will kill for. Or die for. Not many people are prepared to kill for Balzac or Bowie, but culture in this more specialised sense also plays a key role in nationalist politics. There are jobs for artists once more, as from Yeats and MacDiarmid to Sibelius and Senghor they become public figures and political activists. In fact, nationalism has been described as the most poetic form of politics. When the British shot some Irish nationalist rebels in 1916, a British army officer is said to have remarked: ‘We have done Ireland a service: we have rid it of some second-rate poets.’

Wanted: Culture, to rival religious faith

The nation itself resembles a work of art, being autonomous, unified, self-founding and self-originating. As this language might suggest, both art and the nation rank among the many surrogates for the Almighty that the modern age has come up with. Aesthetic culture mimics religion in its communal rites, priesthood of artists, search for transcendence and sense of the numinous. If it fails to replace religion, this is, among other things, because culture in the artistic sense involves too few people, while culture in the sense of a distinctive way of life involves too much conflict. No symbolic system in history has been able to rival religious faith, which forges a bond between the routine behaviour of billions of individuals and ultimate, imperishable truths. It’s the most enduring, deep-rooted, universal form of popular culture that history has ever witnessed, yet you won’t find it on a single cultural studies course from Sydney to San Diego.

For the liberal humanist heritage, culture mattered because it represented certain fundamental, universal values that might constitute a common ground between those who were otherwise divided. It was a ground on which we could converge simply by virtue of our shared humanity, and in this sense it was an enlightened notion; you didn’t have to be the son of a viscount to take part. Since our shared humanity was rather an abstract concept, however, something that brought it back to lived experience was needed, something you could see and touch and weigh in your hand: this was known as art or literature. If someone asked you what you lived by, you gave them not a religious sermon or a political pamphlet but a volume of Shakespeare.

The self-interest of this project, as with almost all appeals to unity, is obvious enough: culture, like the bourgeois state for Marx, represents an abstract community and equality which compensate for actual antagonisms and inequities. In the presence of the essential and universal, we are invited to suspend superficial distinctions of class, gender, ethnicity and the like. Even so, liberal humanism captured a truth, albeit in a self-serving form: what human beings have in common is in the end more important than their differences. It’s just that, politically speaking, the end is a long time coming.

Wanted: Culture, to make profits and fight wars for political demands

The vision of culture as common ground was challenged from the late 1960s by a series of developments. Students were entering higher education from backgrounds that made them disinclined to sign up to this consensus. The concept of culture began to lose its innocence. It had already been compromised by its association with racist ideology and imperialist anthropology in the 19th century, and contaminated by political strife in the context of revolutionary nationalism. From the end of the 19th century, culture became a highly lucrative industry, as cultural production was increasingly integrated into production in general, and the manufacture of mass fantasy became deeply profitable. This, we might note, isn’t yet postmodernism. Postmodernism happens not just with the arrival of mass culture but with the aestheticising of social existence, from design and advertising to branding, politics as spectacle, tattoos, purple hair and ridiculously large glasses. Culture, once the antithesis of material production, has now been folded into production.

Modernism, now a century behind us, was the last time culture offered itself as a full-blooded critique of society, a critique launched mainly from the radical right. If it does so no longer, neither does culture in the sense of a specific form of life. Most such life-forms today are out not to question the framework of modern civilisation but to be included within it. Inclusion, however, isn’t a good in itself, any more than diversity is. One thinks fondly of Samuel Goldwyn’s cry: ‘Include me out!’

All of this is sometimes known as cultural politics, and has given rise in our time to the so-called culture wars. For Schiller and Arnold, the phrase ‘culture wars’ would have been an oxymoron like, say, ‘business ethics’ (Beckett is said to have remarked that he had a strong weakness for an oxymoron). Culture in their eyes was the solution to strife, not an example of it. Now, culture is no longer a way of transcending the political but the language in which certain key political demands are framed and fought out. From being a spiritual solution, it has become part of the problem. And we have shifted in the process from culture to cultures.

Both types of culture are currently under threat from different kinds of levelling. Thinking about aesthetic culture is increasingly shaped by the commodity form, which elides all distinctions and equalises all values. In some postmodern circles, this is celebrated as anti-elitist. But distinctions of value are a routine part of life, if not between Dryden and Pope then between Morrissey and Liam Gallagher. In this respect, anti-elitists who like to see themselves as close to common life are deluded. At the same time, cultures in the sense of distinctive forms of life are levelled by advanced capitalism, as every hairdressing salon and Korean restaurant on the planet comes to look like every other, despite the prattle about difference and diversity. In an era when the culture industry’s power is at its most formidable, culture in both of its main senses is being pitched into crisis.

Culture in our time has become nothing less than a full-blooded ideology, generally known as culturalism. Along with biologism, economism, moralism, historicism and the like, it is one of the major intellectual reductionisms of the day. On this theory, culture goes all the way down. The nature of humanity is culture. Behind this doctrine lurks an aversion to nature (one of culture’s traditional antitheses) as obdurate, inflexible, brutely given and resistant to change. At precisely the point where nature is capricious, unpredictable and alarmingly fast-moving, culturalism insists on regarding it as inert and immobile.

It’s not that culture is our nature, but that it is of our nature. It’s both possible and necessary because of the kinds of body we have. Necessary, because there’s a gap in our nature that culture in the sense of physical care must move into quickly if we are to survive as infants. Possible, because our bodies, unlike those of snails and spiders, are able to extend themselves outward by the power of language or conceptual thought, as well as by the way we are constructed to labour on the world. This prosthesis to our bodies is known as civilisation. The only problem, as Greek tragedy was aware, is that we can extend ourselves too far, lose contact with our sensuous, instinctual being, overreach ourselves and bring ourselves to nothing. But that’s another story.

This video of the lecture is worth watching not only for the Q and A session, but for Terry's closing rendition in song of Raglan Road

Terry Eagleton is a British literary theorist, critic, and public intellectual. He is currently Distinguished Professor of English Literature at Lancaster University. He has published over forty books, anmd hundreds of articles and reviews, and is the most influential contemporary cultural theorist.

Fran Lock is an editor, essayist, the author of numerous chapbooks and thirteen poetry collections, most recently Hyena! (Poetry Bus Press), which was shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize 2023. She is a Commissioning Editor at Culture Matters, and she edits the Soul Food column for Communist Review.

Alan Morrison is a Sussex-based poet. His collections include A Tapestry of Absent Sitters (2009), Keir Hardie Street (2010; shortlisted for the 2011 Tillie Olsen Award, Working-Class Studies Association, USA), Captive Dragons (2011), Blaze a Vanishing (2013), Shadows Waltz Haltingly (2015), Tan Raptures (2017), Shabbigentile (2019), Gum Arabic (2020), Anxious Corporals (2021), Green Hauntings (2022), Wolves Come Grovelling (2023) and Rag Argonauts (2024). He was joint winner of the 2018 Bread & Roses Poetry Award, and was highly commended in the inaugural Shelley Memorial Poetry Competition 2022. He edits The Recusant and Militant Thistles, and is book designer for Culture Matters.